This article originally appeared in the Winter 2016 issue of Carologue.

Portrait of John Laurens, a major character in Hamilton, from the SCHS Visual Materials Collection.

Though there are no signs that the attention surrounding the smash Broadway musical Hamilton is fading anytime soon, I will not throw away my shot at highlighting a few remarkable items from the SCHS holdings that are related to the story behind it. Inspired by the 2004 Ron Chernow biography Alexander Hamilton, the Lin-Manuel Miranda-penned musical traces the tumultuous life of the “ten-dollar founding father” while also starring the authors of some of the most prized letters in our collections, including George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and the Marquis de Lafayette. In fact, the society’s flagship Henry Laurens Papers contain dozens of letters written by “America’s favorite fighting Frenchman” from 1777 to 1781 concerning topics that range from a proposed expedition to Canada in 1778 to French soldiers offering their services to Congress.

As for Aaron Burr, the musical’s narrator (and Hamilton’s nemesis), the SCHS has several items on the hotly contested presidential election of 1800, which resulted in an electoral tie between Jefferson and Burr and also provides a pivotal turning point in the second act. In a letter dated December 12, 1800, for instance, Elizur Goodrich reported to Timothy Pitkin that the electors for Jefferson and Burr in South Carolina were chosen by a majority of thirteen, though “it would have been easy to have made a Union for Jefferson and [Charles Cotesworth] Pinckney.” The 1783 birth of Burr’s daughter is the impetus for a moving ballad performed in Hamilton’s first act, but Theodosia Burr Alston made her mark on South Carolina history when she famously vanished aboard the ill-fated Patriot in December 1812, just weeks after her husband became the state’s forty-fourth governor. Interesting secondary materials on her life and mysterious disappearance can be found in the Alston-Pringle-Frost Papers and a vertical file dedicated to her.

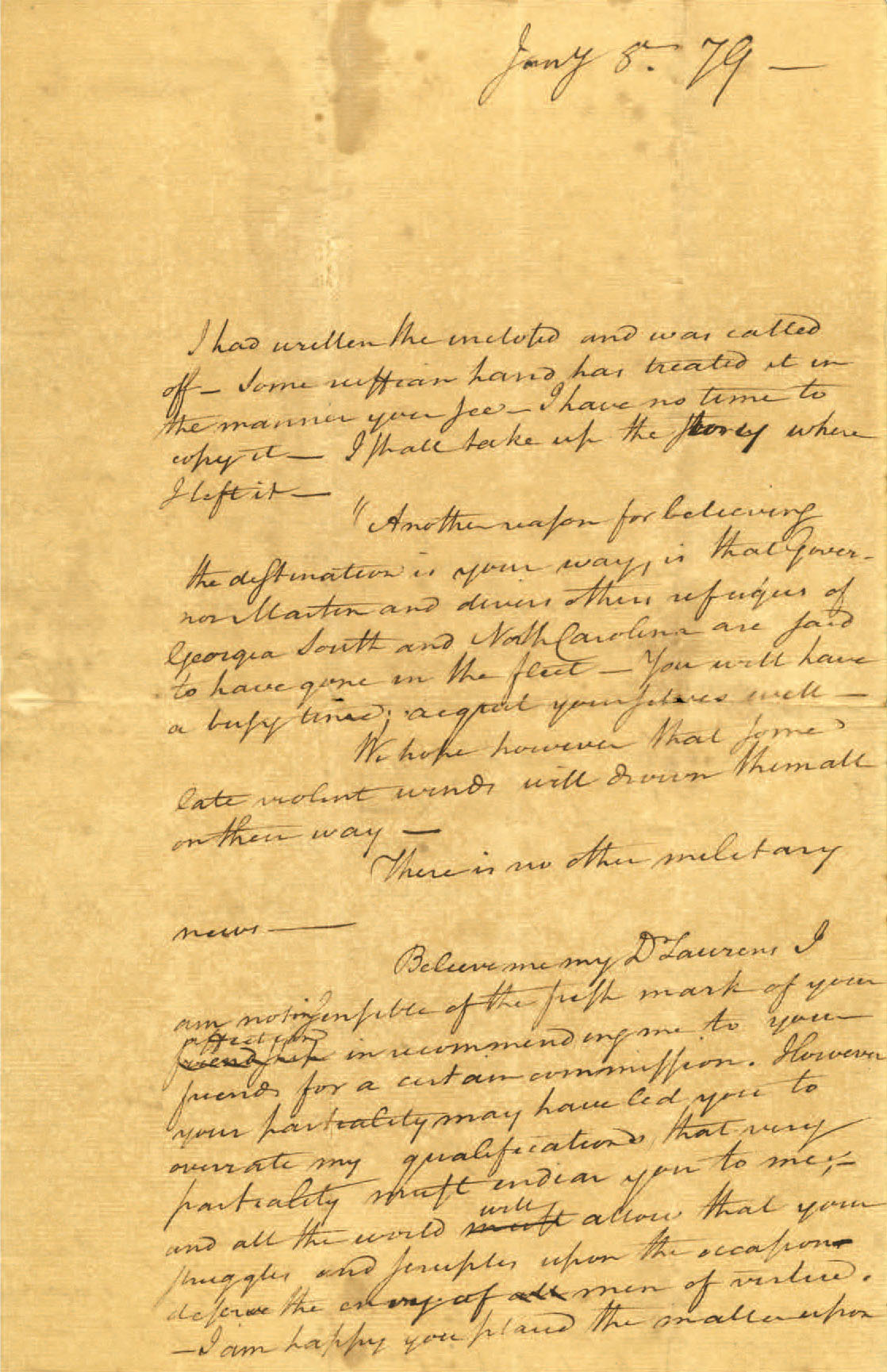

Perhaps most intriguing to Hamilton fans, however, will be the letters written by the future treasury secretary himself to John Laurens, who figures prominently in the show as Hamilton’s closest friend. Born in Charleston in 1754, Laurens was the eldest son of Henry Laurens and Eleanor Ball and served at various times in his short life as a Revolutionary War officer, a member of the South Carolina House of Representatives, and a special minister to France. Notably, he was also a strong opponent of slavery and even proposed that the state arm and emancipate slaves in return for their military service. Included within Laurens’s papers at the SCHS is a fascinating letter from January 1780 (incorrectly dated 1779) in which Hamilton referenced a British fleet departing New York before discussing Laurens’s (unsuccessful) recommendation to Congress that Hamilton be named secretary to the American minister plenipotentiary at Versailles:

January 1780 letter written to John Laurens by Alexander Hamilton from the SCHS’s John Laurens Papers.

I had written the enclosed and was called off. Some ruffian hand has treated it in the manner you see. I have no time to copy it. I shall take up the story where I left it.

Another reason for believing the destination is your way, is that Governor Martin and divers others refugees of Georgia South and North Carolina are said to have gone in the fleet. You will have a busy time; acquit yourselves well. We hope however that some late violent winds will drown them all on their way. There is no other military news.

Believe me my Dr Laurens I am not insensible of the first mark of your affection in recommending me to your friends for a certain commission. However your partiality may have led you to overrate my qualifications that very partiality must endear you to me; and all the world will allow that your struggles and scruples upon the occasion deserve the envy of men of vertue. I am happy you placed the matter upon the footing you did, because I hope it will ultimately engage you to accept the appointment. Had it fallen to my lot, I should have been flattered by such a distinction but I should have felt all your embarrassments.

Of this however I need have no apprehension. Not one of the four in nomination but would stand a better chance than myself; and yet my vanity tells me they do not all merit a preference. But I am a stranger in this country. I have no property here, no connexions. If I have talents and integrity, (as you say I have) these are justly deemed very spurious titles in these enlightened days, when unsupported by others more solid; and were it not for your example, I should be inclined in considering the composition of a certain body, to suppose that three fourths of them are mortal enemies to the first and three fourths of the other fourth have a laudable contempt for the last.

In closing the letter, Hamilton mentioned that he had been dissuaded from seeking a field command (therefore providing “the only extant evidence” that he was doing so at that time, according to the editors of The Papers of Alexander Hamilton) and also touched on his desire to “make a brilliant exit”:

I have strongly sollicited leave to go to the Southward. It could not be refused; but arguments have been used to dissuade me from it, which however little weight they may have had in my judgment gave law to my feelings. I am chagrined and unhappy but I submit. In short Laurens I am disgusted with every thing in this world but yourself and very few more honest fellows and I have no other wish than as soon as possible to make a brilliant exit. ’Tis a weakness; but I feel I am not fit for this terrestreal Country.

All the Lads embrace you. The General sends his love. Write to him as often as you can.

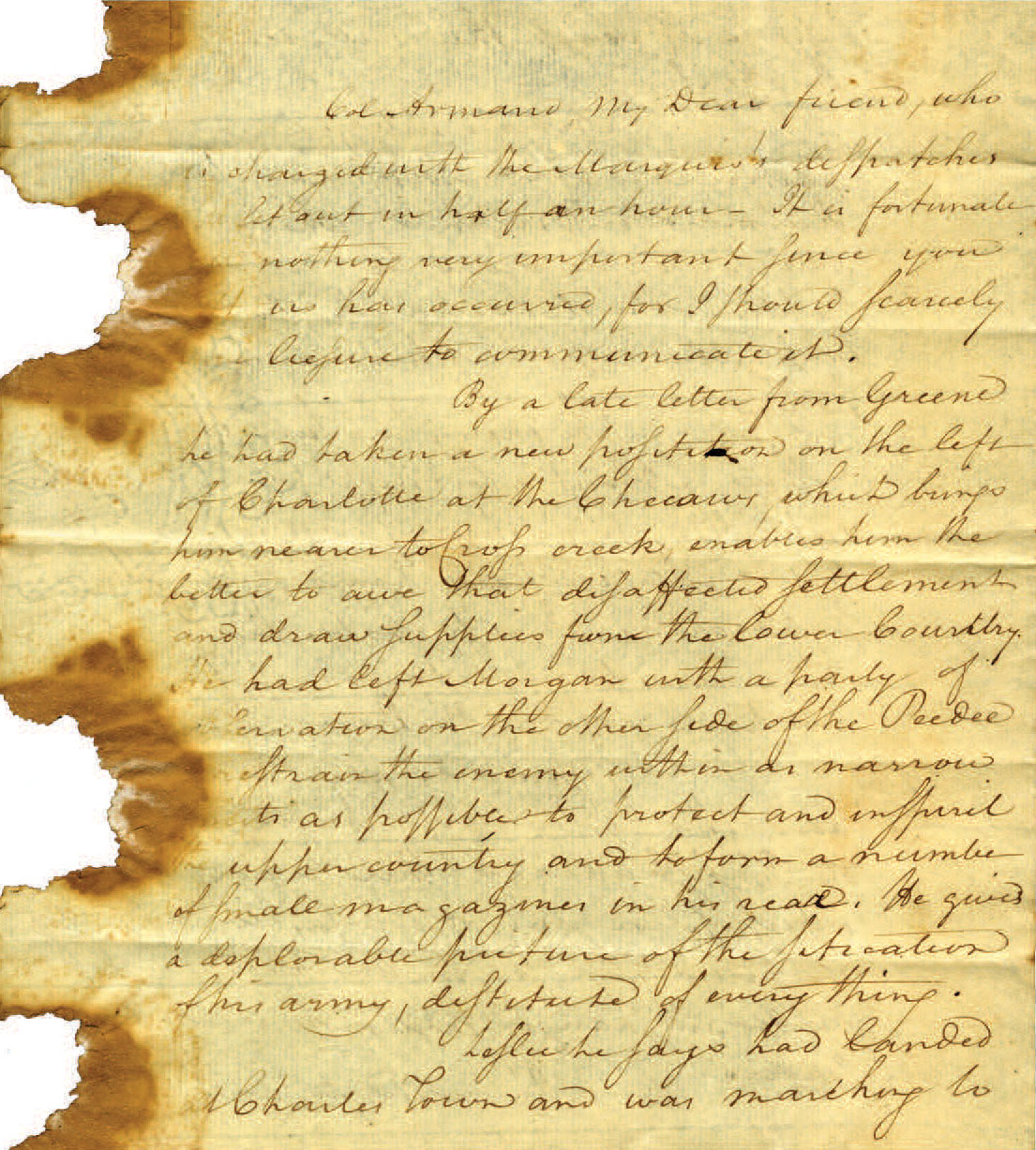

February 1781 letter written to John Laurens by Alexander Hamilton from the SCHS Discrete Manuscripts Collection.

In another letter that is part of the society’s Discrete Manuscripts Collection and dated February 4, 1781, Hamilton wrote to Laurens about the movements and operations of the British and Continental armies in South Carolina, Virginia, and Pennsylvania as well as a proposal by his father-in-law, Philip Schuyler, for “a solid confederation to give sufficient powers to Congress for calling forth the resources of the country … for the support of the war.” Hamilton then concluded with an assurance to his friend that it would be “impossible more ardently to wish for your health safety pleasure and success” than he did. Sadly, Laurens was killed at the Battle of the Combahee River on August 27, 1782, just eighteen months after the letter was written, but this South Carolinian’s story is now being introduced to a whole new twenty-first-century audience thanks to Hamilton.