Phone: (843) 723-3225

Museum: 100 Meeting St.

Archives: 205 Calhoun St.

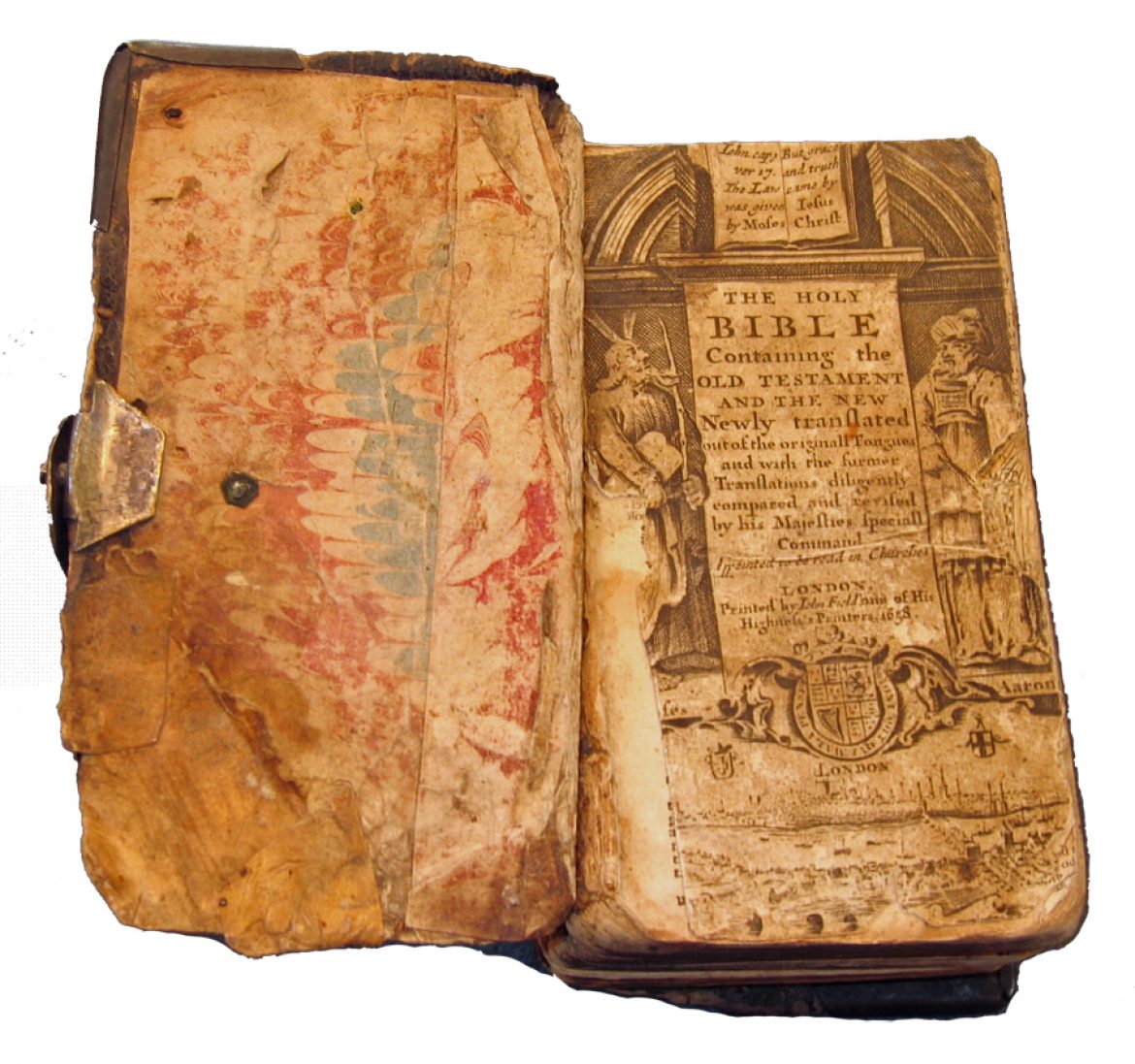

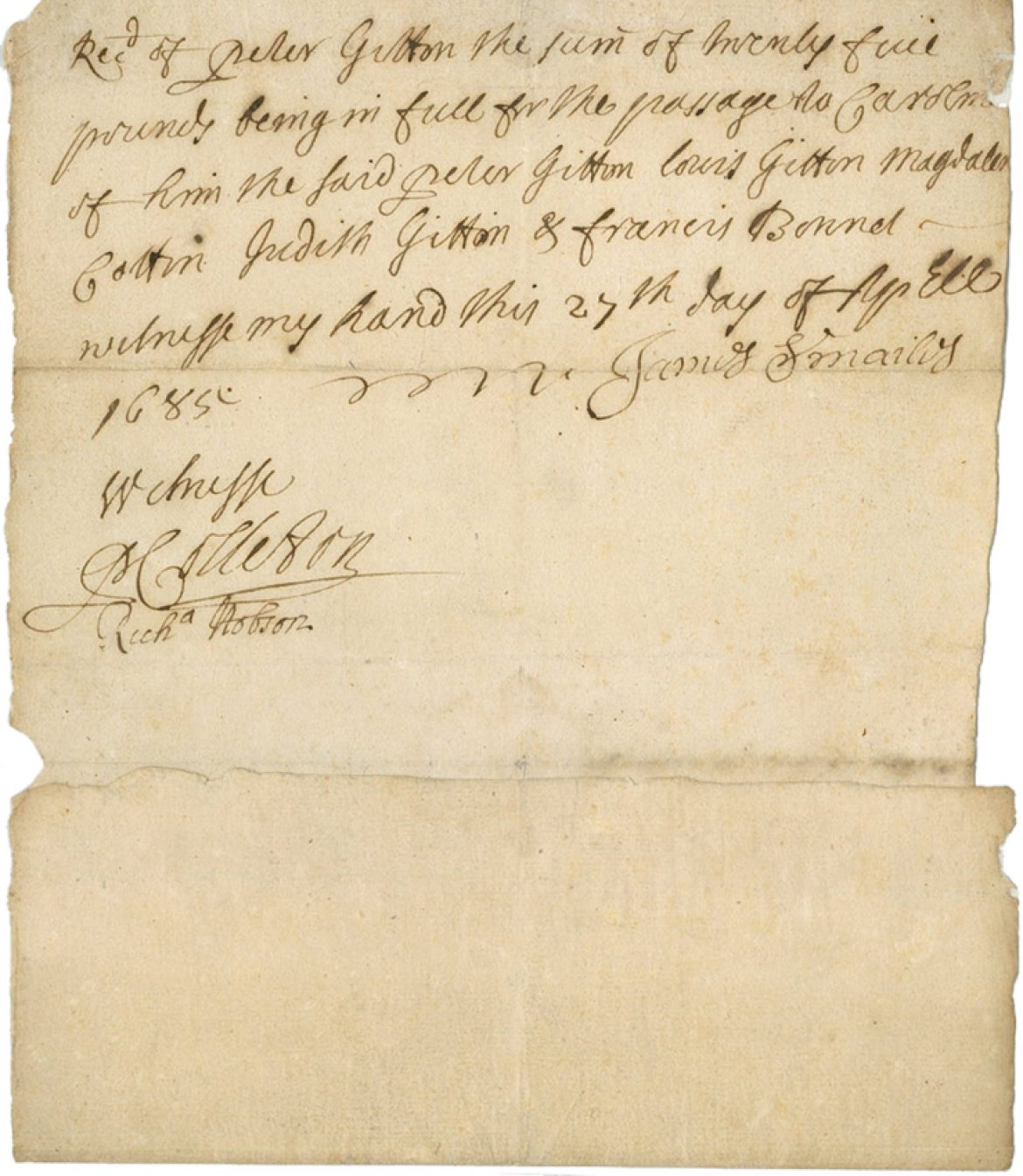

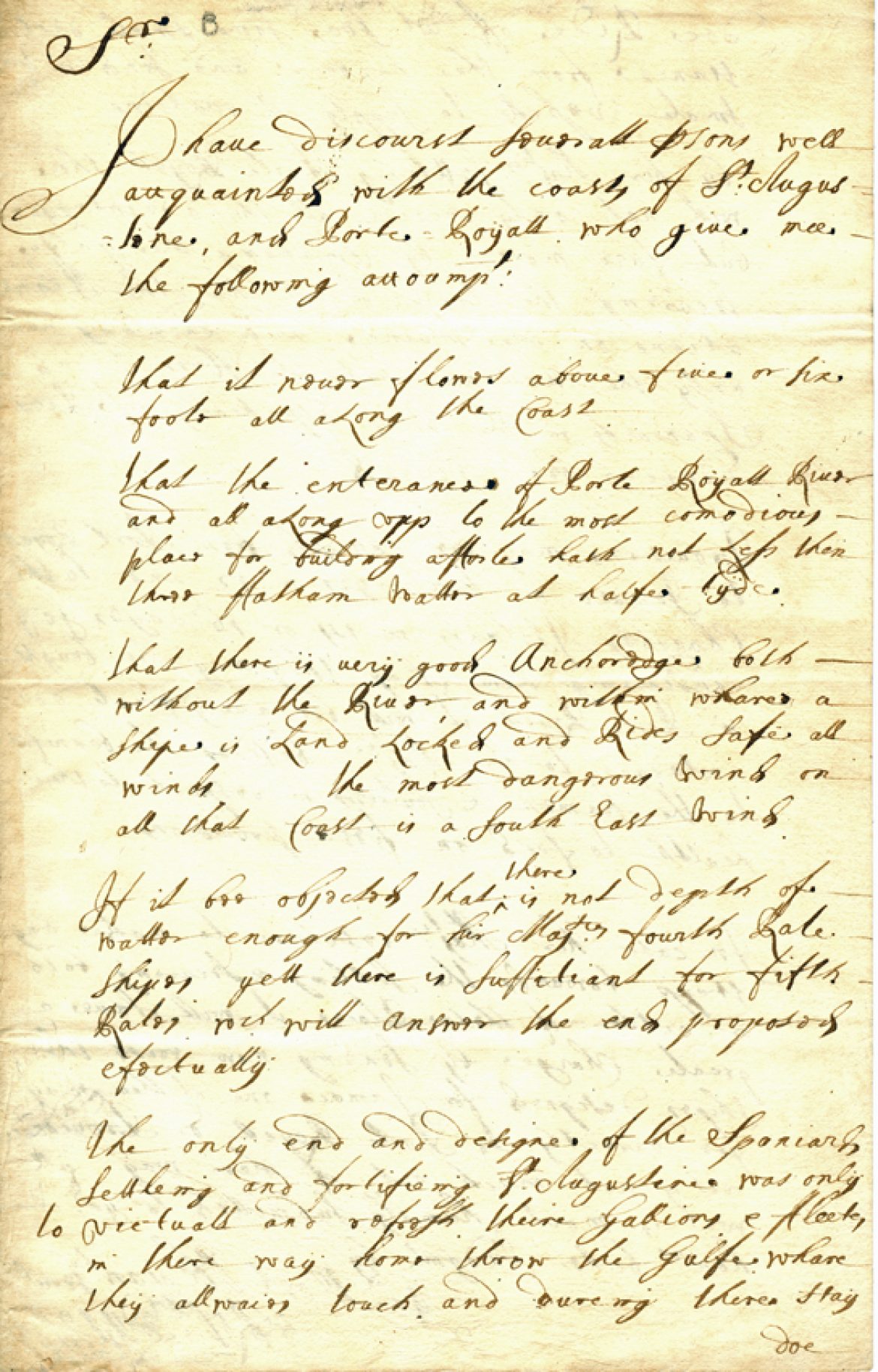

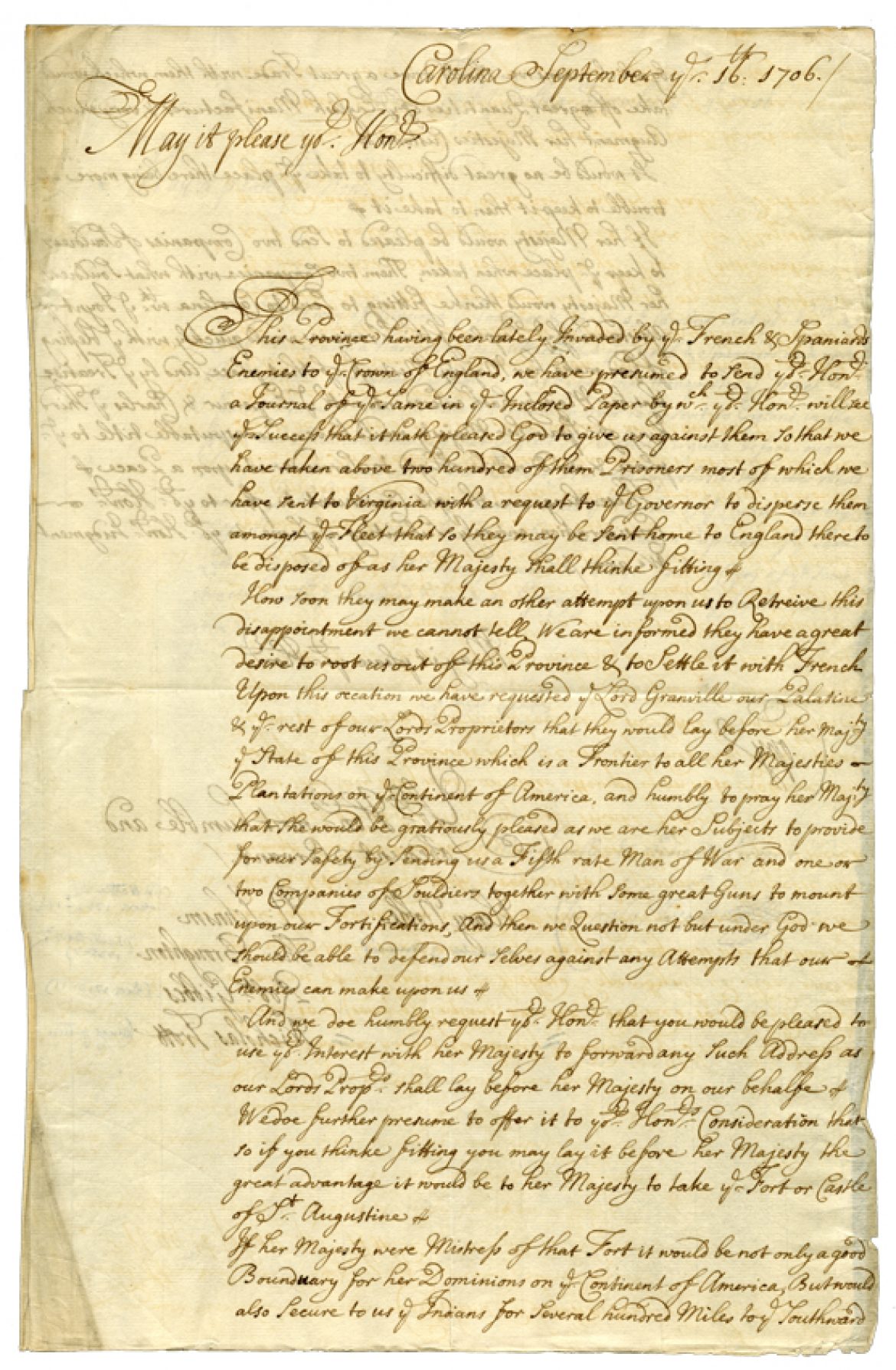

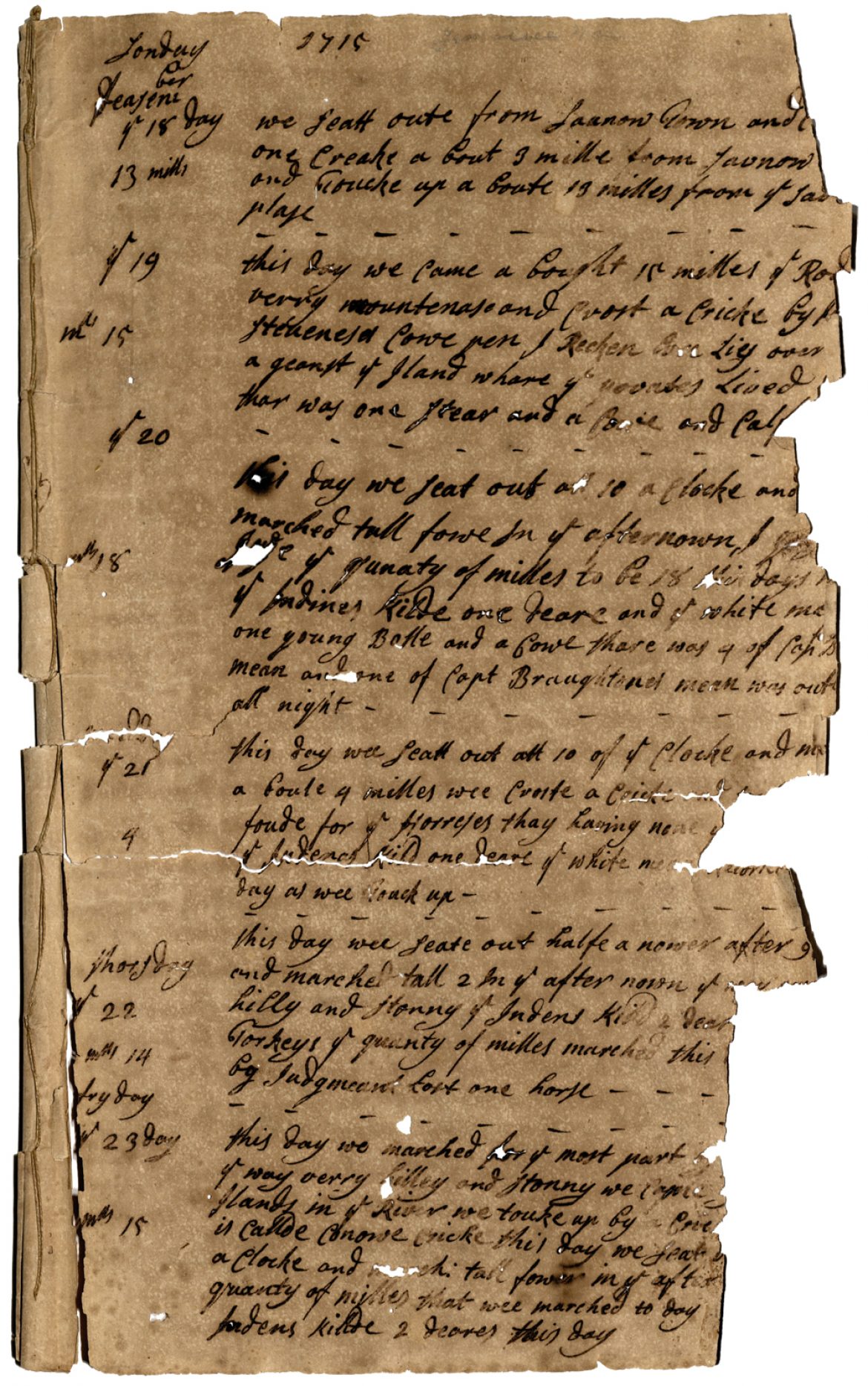

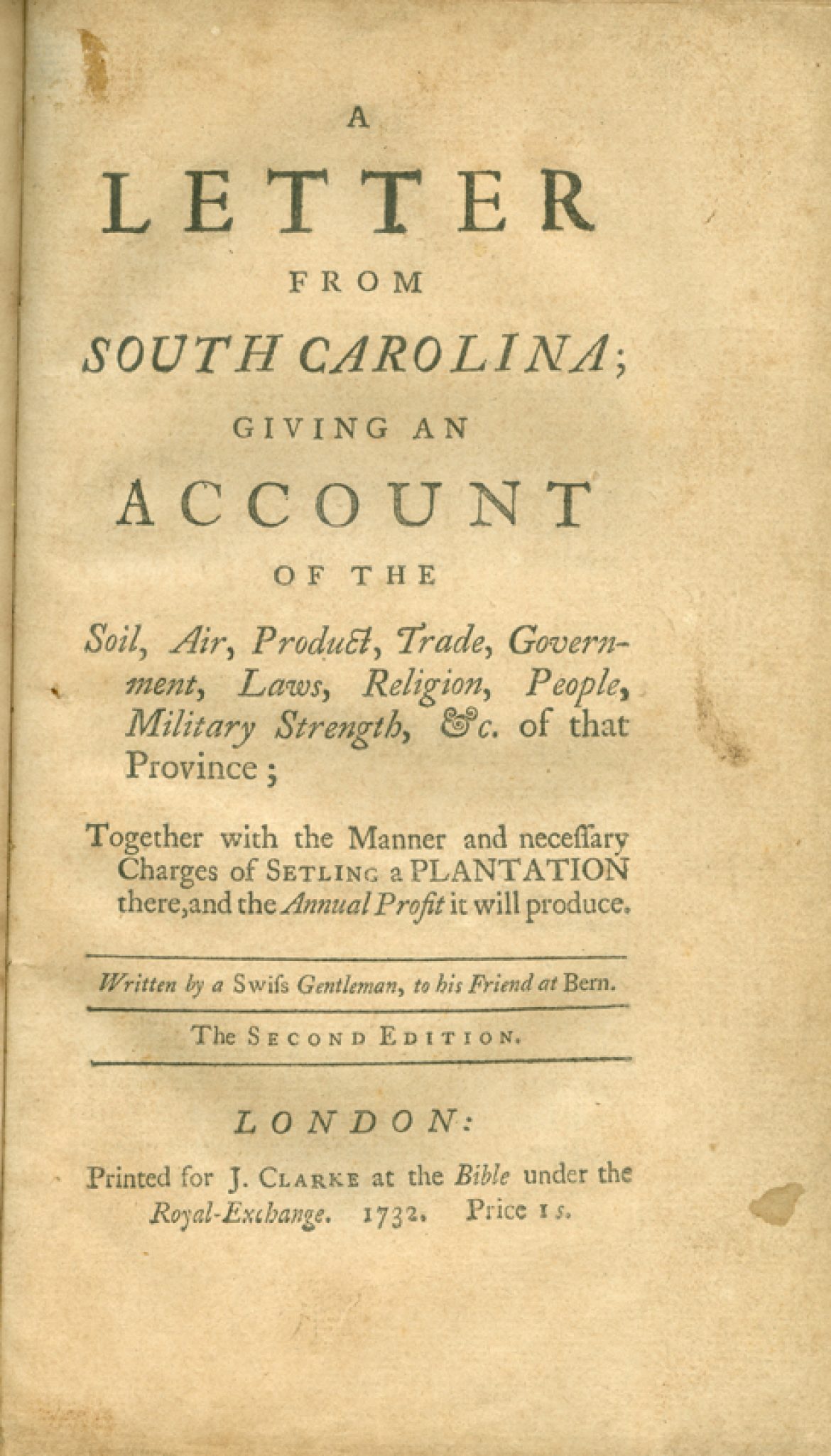

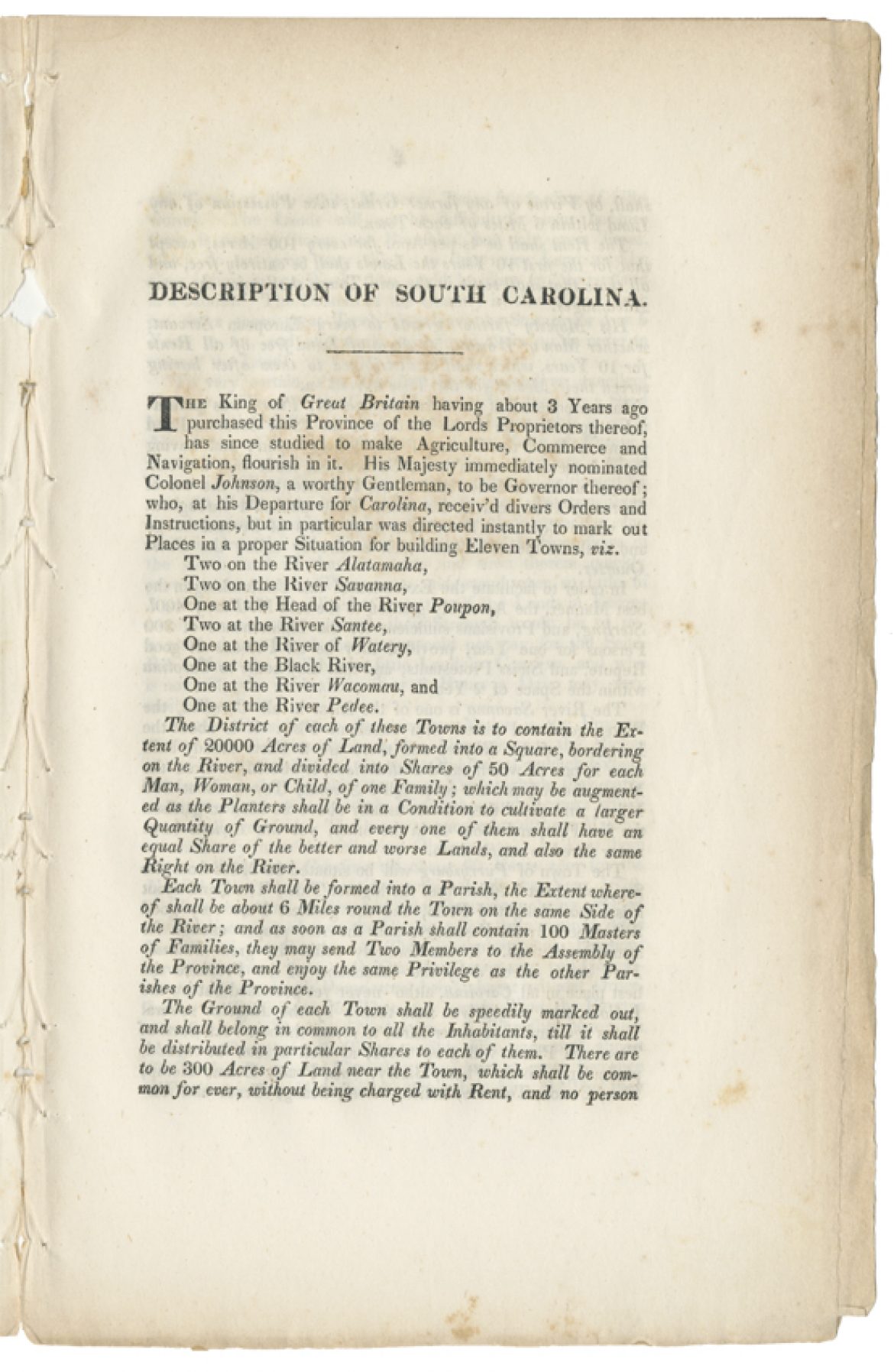

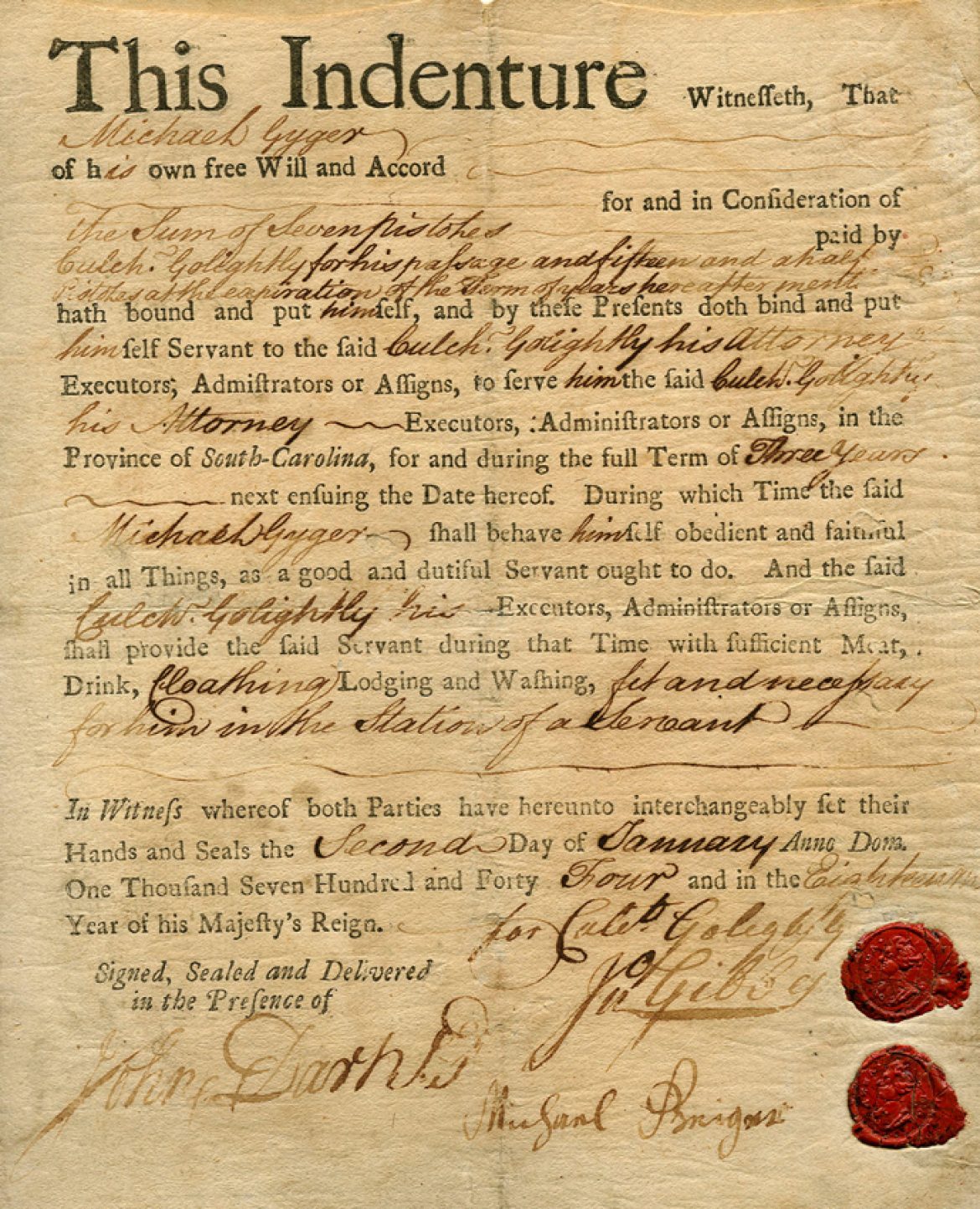

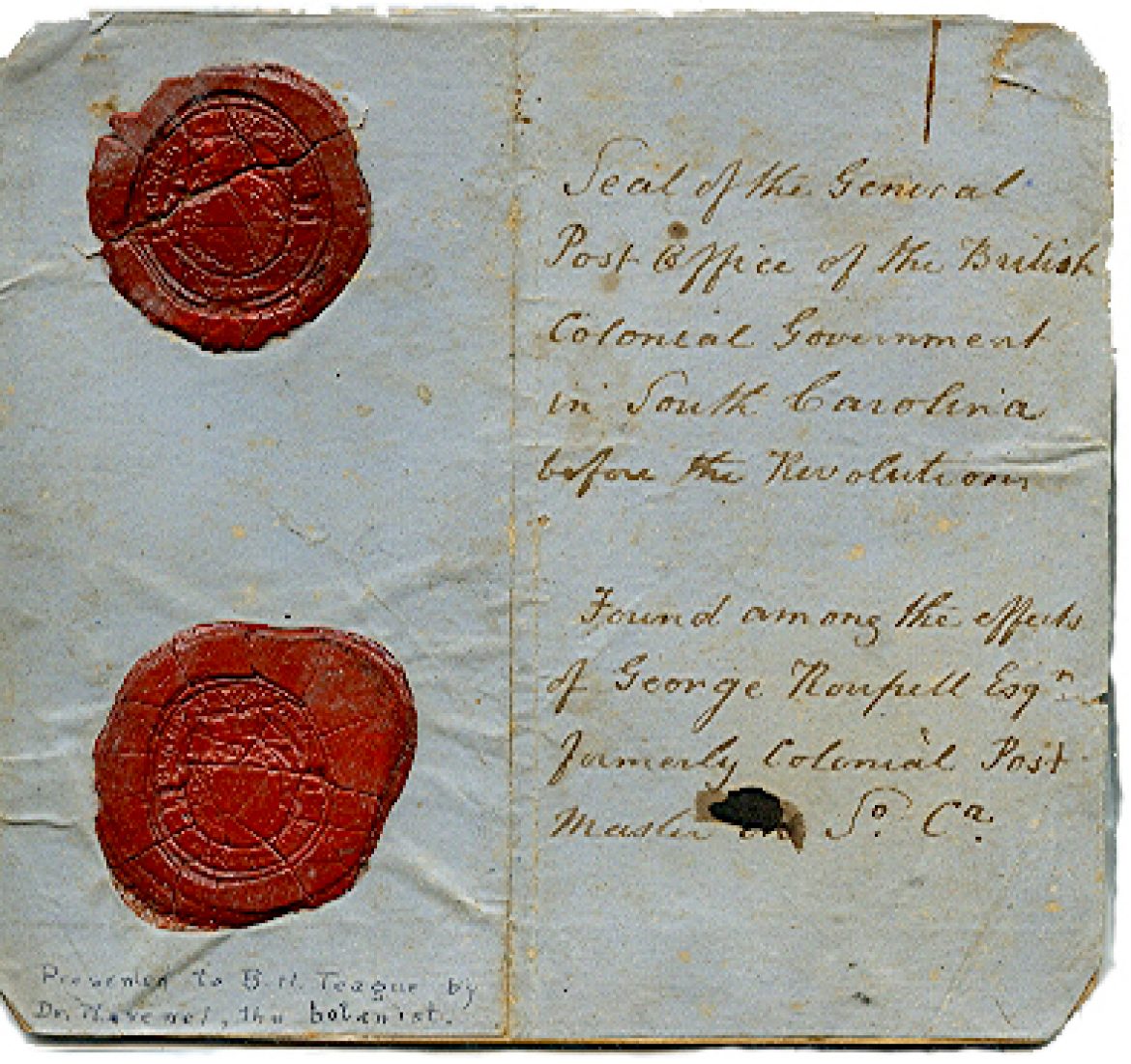

A Glimpse at Colonial Migration and Movement in South Carolina

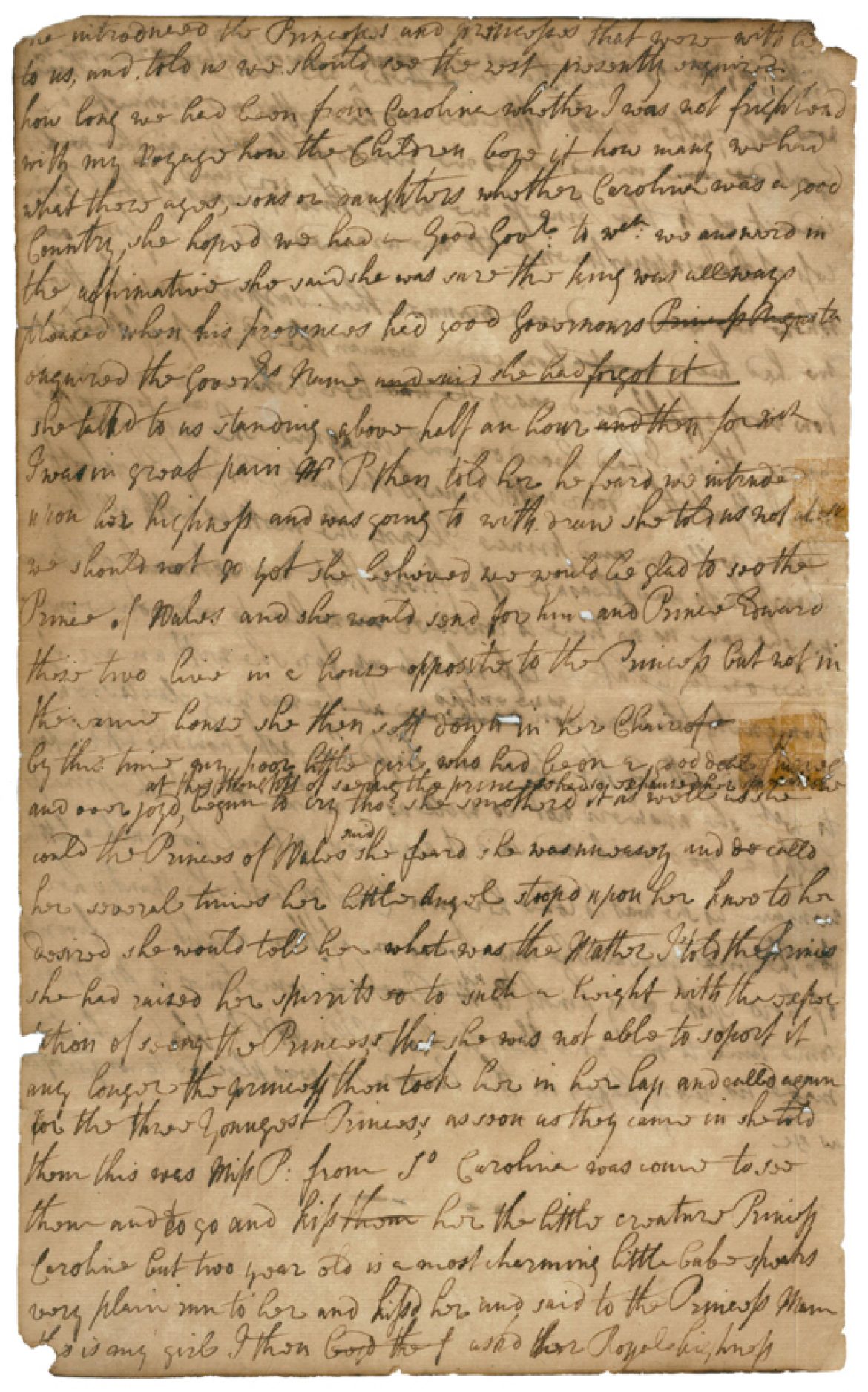

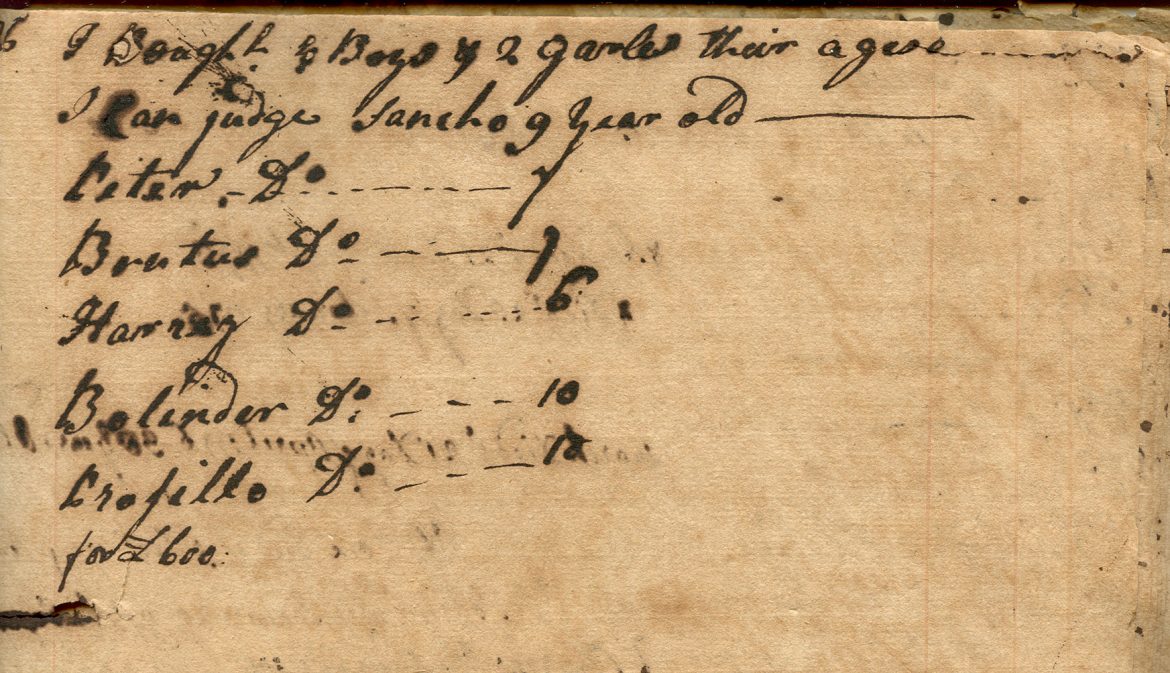

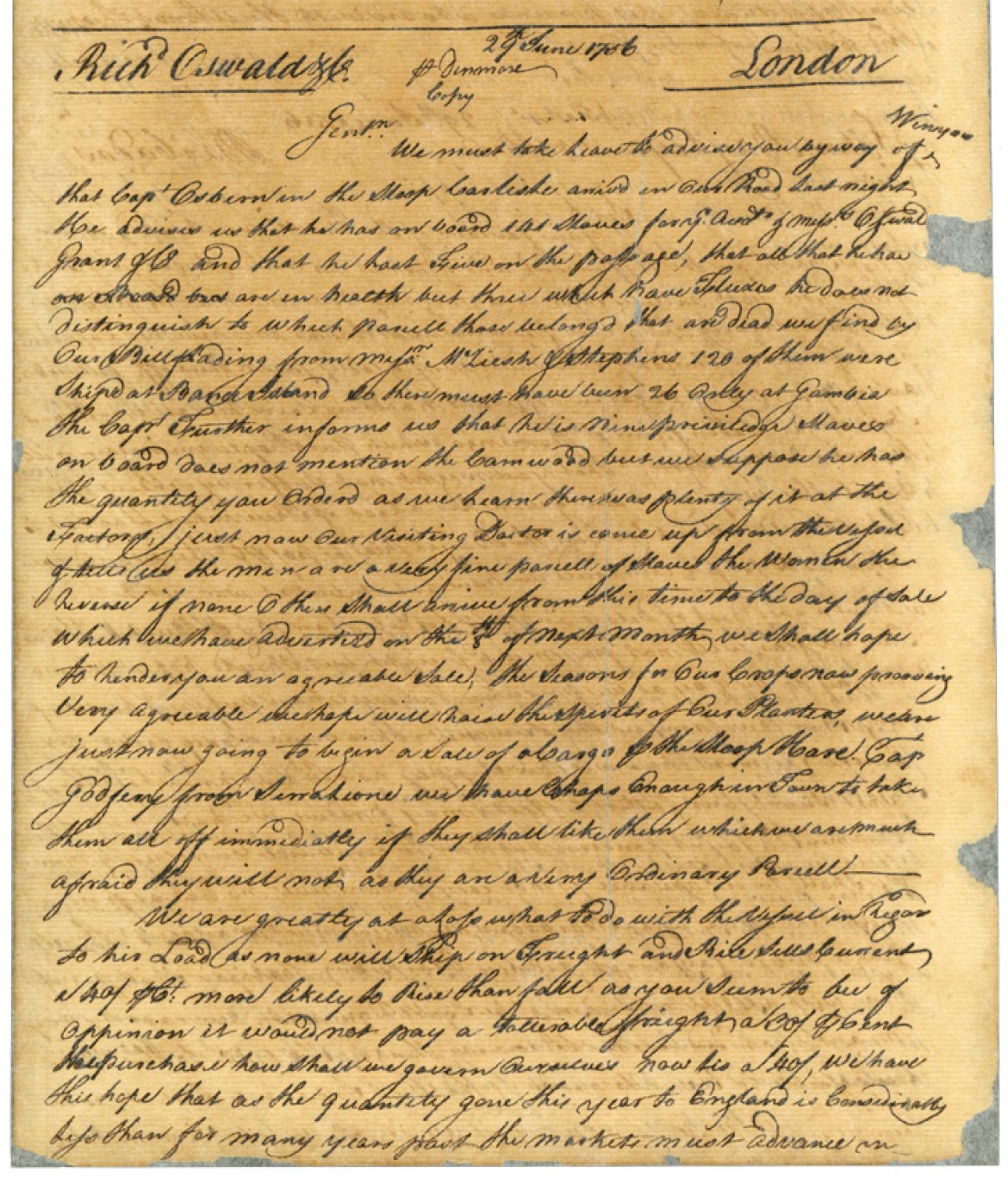

From its first days as an English colony, South Carolina was an economic frontier and a religious haven. Once proclaimed throughout England and Europe, that freedom was as much a beacon for Nonconformist (non-Anglican) Protestant, French Huguenot, and Jewish immigrants as were promises of cheap land and economic opportunity. The society’s collections hold many pieces of evidence describing conditions, environmental and social, as colonists ventured to and from South Carolina.