Image from Acts of the General Assembly of South-Carolina (1783-1786) from the collections of the South Carolina Historical Society.

The American Revolution presented enslaved people an opportunity to gain their freedom if they joined the British forces or spied for the American side. A handful of primary sources document the actions of a few enslaved spies who served the American cause. One of them was a man named Antigua (alternatively spelled Antego and Antigo) who was enslaved by John Harleston (1755/56 -1781) of St. John’s Parish in Berkeley County. Harleston’s will made provisions for Antigua’s freedom as his “reward for his great attachment to my person and interests, and his ready and faithful discharge of duty to me in every capacity.”

During the Revolution, Antigua worked with Governor John Rutledge “for the purposes of procuring information of the enemy’s movements and designs.” By infiltrating British encampments, Antigua was able to access intelligence valuable to the American forces. In September 1781, during the British occupation of Charleston, Rutledge sent letters to merchants who were under British protection but not Loyalists. The letters contained a proposal beneficial to both the merchants and the Patriot cause. Antigua was carrying the letters when he was captured by the British who seized the letters and published them in the Royal Gazette. What happened to Antigua immediately after this incident is unknown.

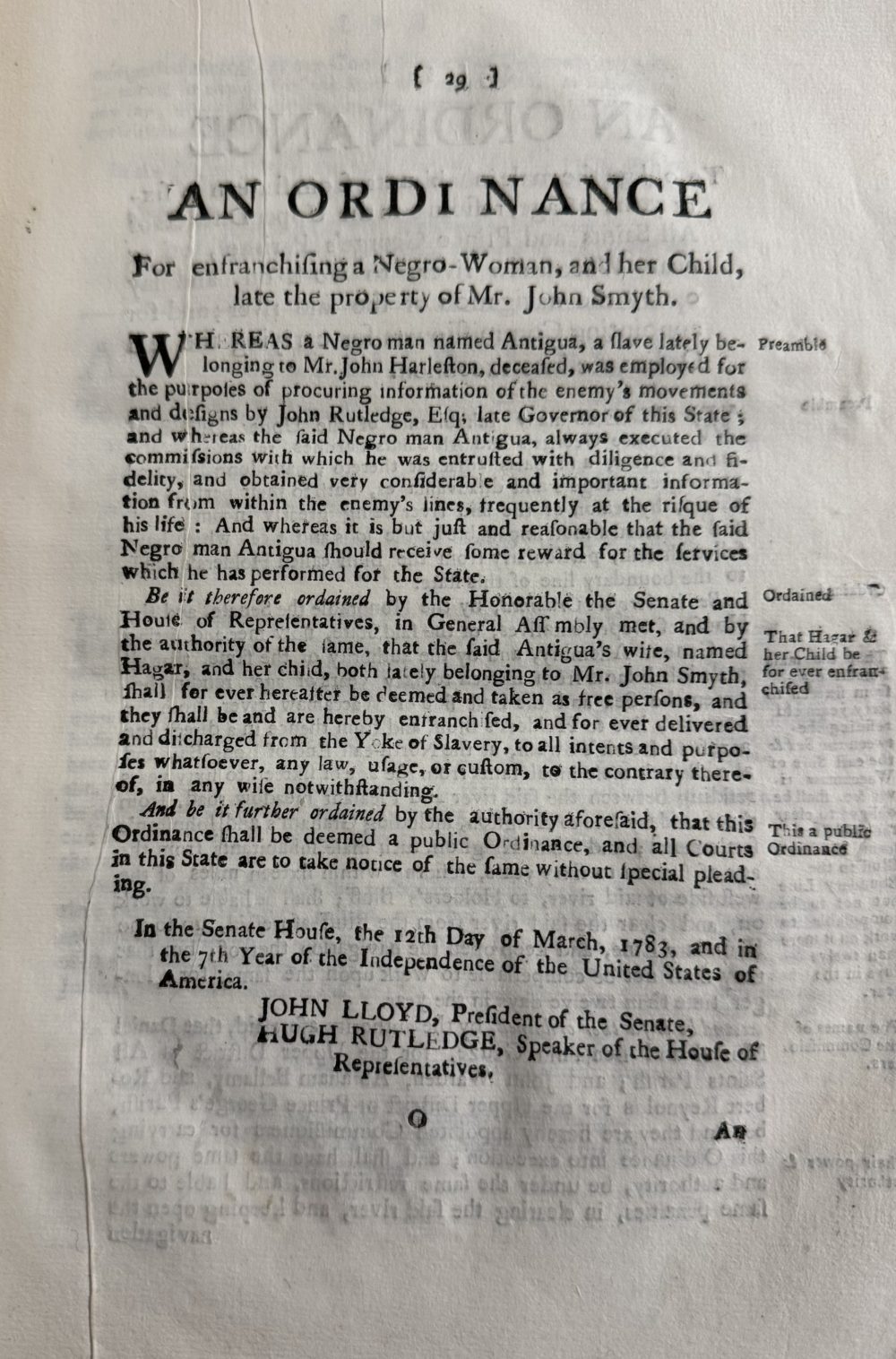

In February 1783, a committee of the South Carolina House of Representatives heard a petition from then former Governor Rutledge recommending the manumission of Antigua’s wife, Hagar, and their child as a reward for his services as a spy. Hagar and the child were owned by Loyalist John Smyth whose property was confiscated at the close of the Revolution.

On March 12, 1783, Hagar and the child were “forever delivered from the yoke of slavery” by the South Carolin General Assembly. Antigua was praised for his skill in “procuring information of the enemy’s movements and designs” and he “always executed the commissions with which he was entrusted with diligence and fidelity…. frequently at the risk of his life.”