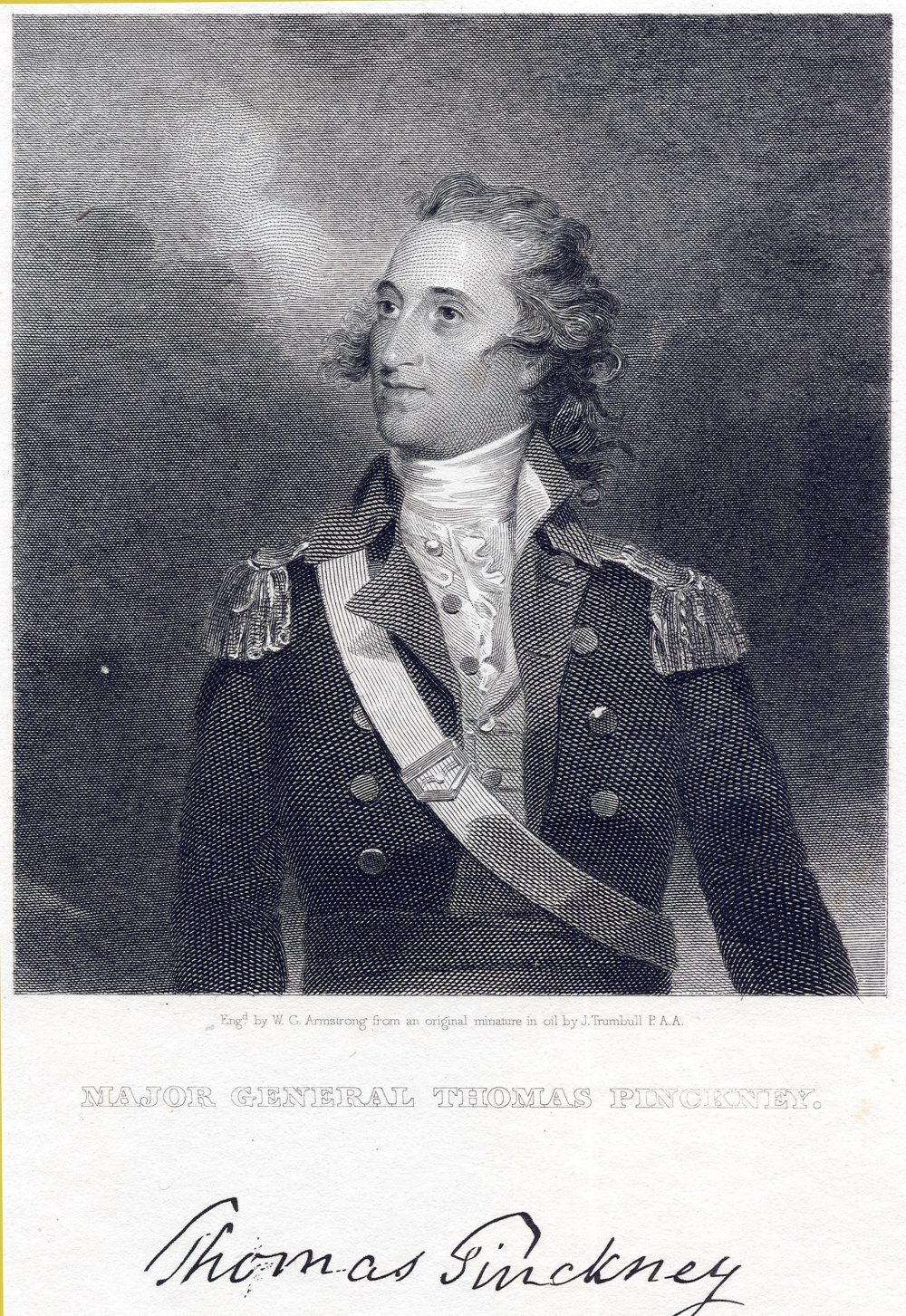

Portrait of Thomas Pinckney. Courtesy of the South Carolina Historical Society.

Thomas Pinckney was the youngest son of Eliza Lucas and Charles Pinckney. Born in 1750, he was placed in school in England when he was three years old. His father died when Thomas was eight and he remained in England until he returned briefly to South Carolina in 1771, at twenty-one years old. By this time, Thomas had graduated from Westminster School and Oxford University, traveled to France, and studied law at Middle Temple. Thomas returned to Charleston in 1774 and was admitted to the South Carolina Bar.

According to his brother’s biographer, Thomas was an ardent supporter of colonial rights. Marvin Zahniser explains that, at Westminster School, both Thomas and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney would have been reminded daily that they were “colonials,” who lacked the status given to the sons of English aristocrats. The reaction of both boys to the Stamp Act in 1765 suggests that they resented the English earlier than their peers in the colonies. Thomas was known to school mates as “the little rebel.”

In 1776, the year after Thomas tried his first case in Charleston, the British responded to the Boston Tea Party with the Coercive Acts. South Carolina answered by raising three regiments of regulars to protect the province. Charles Cotesworth Pinckney was selected to be captain of one of them and recruited Thomas to join his company. The Council of Safety ordered the seizure of Ft. Johnson, which was the fort on James Island that guarded Charleston Harbor. It was occupied on Sept. 15 by a force quickly assembled by William Moultrie which included Pinckney’s company. The following June, when the British attacked and were repelled in the now-famous Battle of Sullivans Island, the Pinckneys, much to their disappointment, were not involved.

After the Battle of Sullivans Island, Thomas was promoted to Major and was assigned recruitment duty. He traveled to Virginia and North Carolina rallying men to sign up for service. Like his brother, he was discouraged because he was not in the center of action. He wrote to his sister Harriott: “you may depend upon there being no fighting wherever I am.” In the spring of 1779, General Lincoln, who led the southern patriot troops, decided to cross the Savannah River and cut British supply lines. As they marched towards Charleston, they burned Thomas’ plantation, Aukland, on the Ashepoo River.

In the summer of 1779, during a brief lull in the Revolution, Thomas married Elizabeth Motte. She was the daughter of Rebecca Brewton Motte, one of the wealthiest women in the colony and a well-known patriot. That fall, Thomas served as a liaison between American and French forces. But early the next year, the British stood poised to advance towards Charleston once more. By May, General Lincoln was forced to surrender the city. The captured officers, including Charles Cotesworth, were sent to Haddrell’s Point. Thomas was away on recruitment duty and avoided capture. He then joined the other continental troops that remained in the Carolinas and became an aide-de-camp to General Horatio Gates. At the Battle of Camden in 1780, Thomas’ leg was shattered by a musket ball, and he was captured. The British paroled him and sent him to Philadelphia and then Virginia.

Following the war, Thomas served in the state House of Representatives. In 1787, he was elected Governor of South Carolina. During his term, he presided over the convention that ratified the Constitution. In 1792, Thomas became the first U.S. Minister to Great Britain. Three years later, he was appointed Envoy to Spain and negotiated “Pinckney’s Treaty,” which established the southern border of the U.S and gave U.S. citizens the right to navigate the Mississippi River. This agreement also forced Spain to recognize freedom of the seas. Thomas also served as a major general in the War of 1812. He is buried in St. Philip’s Church Cemetery in Charleston.