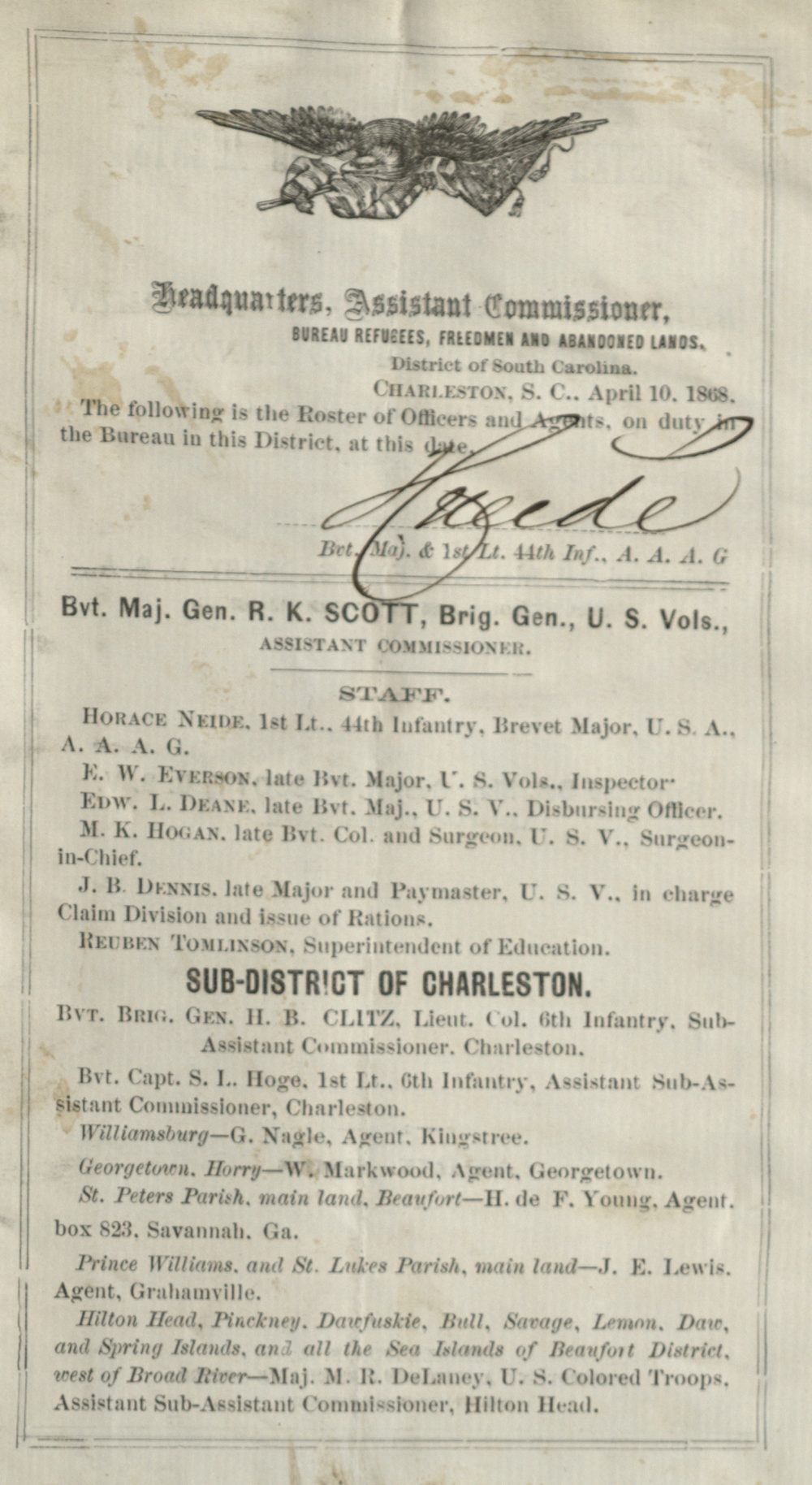

Image of a roster of officers and agents in the Freedmens Bureau in South Carolina from April 10, 1868. From the collections of the South Carolina Historical Society.

In February of 1865, President Abraham Lincoln commissioned Martin Robison Delany as an officer in the Union Army. At the age of fifty-two, Delany became the first Black Major in the United States Army and was assigned to Hilton Head, South Carolina. He would spend over a decade in South Carolina working to improve political, economic, and educational opportunities for the formerly enslaved while leaving an indelible mark on South Carolina politics and its people.

Martin Delany’s pre-military experiences were varied and impressive. Delany was born in Charles Town, Virginia (now West Virginia) on May 6, 1812. As the youngest of five children born to a free seamstress and an enslaved carpenter, Delany was born free and learned to read and write despite Virginia laws prohibiting the education of Black children. His family relocated to Chambersburg, Pennsylvania and Delany moved once again to Pittsburgh as a teenager to continue his education. There, he held leadership positions in several political and philanthropic societies. Delany published The Mystery, a weekly abolitionist newspaper, and went on to co-edit The North Star newspaper with Frederick Douglass. He studied medicine and was admitted to Harvard Medical School in 1850; however, he and two other Black students were forced to withdraw due to protests by white peers.

The passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 diminished Delany’s outlook on the future for Black people—both free and enslaved— in the United States. He intensified his abolitionist and Black nationalist activism, leading the National Emigration Convention of 1854 and traveling to Liberia and Nigeria in search of lands for Black colonization. Unable to see a free and equitable future for Black Americas in the United States, Delany, his wife, and children settled in Canada and urged others to follow suit.

Delany returned to the United States at the outbreak of the Civil War. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation restored Delany’s belief in the possibility for racial integration in the US. He proposed the creation of a Black military force commanded by Black officers to guarantee the Emancipation Proclamation’s promises of freedom to the formerly enslaved. Delany secured a meeting with President Lincoln to plead his case in February of 1865. The president agreed with his recommendation and commissioned Delany as a Major in the United States Army—the first Black person to achieve that rank. Shortly after, Delany headed to South Carolina on assignment to recruit for the war effort.

Martin Delany spent the next fifteen years in South Carolina. While stationed in Hilton Head and Charleston, Major Delany traveled throughout the Lowcountry to recruit formerly enslaved men to the 103rd, 104th, and 105th regiments of the United States Colored Troops. After war’s end, Delany became a sub-assistant commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, a government agency created to assist newly freed African Americans. Delany’s district was headquartered in Hilton Head and encompassed the surrounding Sea Islands. In this position, he protected and enforced Black civil rights, advocated for increased funding for education, and attempted to secure property rights for formerly enslaved people. In articles and speeches during this time, he promoted economic independence and self-sufficiency.

When the Freedmen’s Bureau disbanded in the late 1860s, Delany continued his service in South Carolina through politics. Delany held multiple political appointments between 1870 and 1880 including Agent of the Bureau of Agricultural Statistics, Customs Inspector, and Trial Justice of Charleston. In 1874, Delany unsuccessfully ran for the state’s second-highest office as the Independent Republican party’s nominee for Lieutenant Governor of South Carolina. His willingness to work with both Republican and Democratic parties in support of Black interests invited controversy and hostility.

Throughout his life, Delany used the press to express his political views despite hostile reactions. In an open letter to his former co-editor, Frederick Douglass, published in February 1876, Delany explained his perspective on political prospects for Black South Carolinians in the context of Reconstruction’s end. Despite his persecution, his column attested to his “faithful adherence to the cause of universal liberty” and advocacy for the rights of all South Carolinians without regard to race, color, or politics. Specifically addressing the formerly enslaved people to whom he dedicated many years, he trusted that they “will stand and thrive, as firmly rooted, not only on the soil of Hilton Head, but in all the South,… as any white, or ‘Live Oak,’ as ever was grown in South Carolina…”

Martin Delany left South Carolina in 1880. The abolitionist, physician, military officer, politician, and journalist died in Ohio on January 24, 1885.