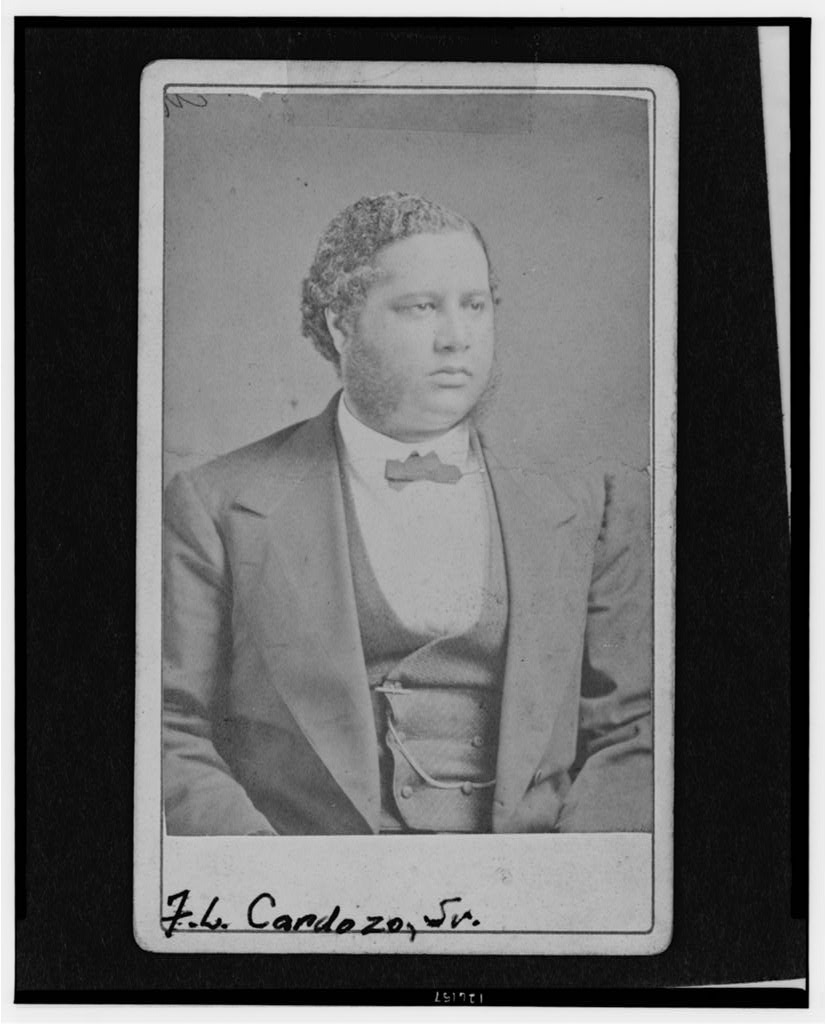

Image of Francis Lewis Cardozo, Sr. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

While South Carolina spearheaded the secessionist movement in 1860 that ignited the Civil War, the state also found itself briefly at the forefront of southern states fulfilling the promise of Reconstruction just eight years later. South Carolina elected the first African American to statewide office in 1868. On July 10th, Francis Lewis Cardozo was sworn in as South Carolina’s Secretary of State.

Francis Cardozo was born in Charleston in 1837. His father, Isaac Cardozo, was a Sephardic Jewish merchant who worked at the United States Custom House. His mother, Lydia Weston, was a formerly enslaved woman who gained her freedom in 1826 and worked as a seamstress. Alongside three siblings, Cardozo grew up in Charleston’s free Black community and was educated at a school for free Black children. At age twenty-one, he set off for the University of Glasgow where he studied Latin, Greek, mathematics, logic, and ethics, followed by three years of training in Scottish and English seminaries. He returned to the United States in 1864 and became the pastor of the African American Temple Street Congregational Church in New Haven, Connecticut.

In 1865, Cardozo returned to South Carolina. With support from the Freedmen’s Bureau and the American Missionary Association, he succeeded his brother as principal of the Tappan School in Charleston, marking the start of his lifelong commitment to expanding educational opportunities for Black students. Upon moving to a new location on St. Philip Street, it was renamed the Saxton Common School and provided primary and secondary education. Under Cardozo’s leadership, the school obtained a permanent building, expanded to include a teacher training school, and was again renamed the Avery Normal Institute, now the Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston.

The 1867 Reconstruction Acts required former Confederate states to adopt new constitutions for readmittance to Congress. Cardozo was overwhelmingly elected to the 1868 State Constitutional Convention where his prior experience propelled him to Chairman of the Education Committee. Major triumphs of the 1868 State Constitution included the institution of statewide public education and the procurement of civil rights and the franchise for African American men. In the following decades, these gains would be systematically dismantled through intimidation, violence, and legislation such as the Eight Box Voting Law enacted in 1882. The 1868 State Constitution, crafted by a delegation of racial parity, was replaced in 1895.

Francis Cardozo served in state government for nearly a decade, first as Secretary of State from 1868-1872, then as State Treasurer from 1872-1877. While Secretary of State, he led the Land Commission Board, which aimed to redistribute land throughout South Carolina to newly freed families. Corruption tempted many members of state government, hampering the administration of the Land Commission among other agencies, but Cardozo did not capitulate. He was well respected by Black and white, Republican and Democrat as a moral arbiter who drew a hard line against corruption. Unfortunately, Cardozo’s overwhelmingly honest reputation made him a target of the next administration.

After the contested presidential election in 1876, the project of Reconstruction was all but abandoned. Since he was considered perhaps the only honorable politician in state government, Cardozo’s prosecution for fraud legitimized allegations of rampant corruption. Cardozo and three of his colleagues, including Robert Smalls, were prosecuted and the testimony of two witnesses, who themselves confessed to involvement in corruption schemes, secured their convictions. After serving seven months in prison, Cardozo was pardoned but not vindicated.

Cardozo and his family relocated to Washington, DC. He later served as the principal of three schools, returning to education but not to South Carolina. He died of heart failure on July 22, 1903, at the age of sixty-six.

The controversy of Reconstruction and the ensuing struggles have long shrouded Francis Cardozo and his legacy. Although Reconstruction remains complicated and fractious, considerable advances in compulsory education, land reform, and voting rights—three of his largest priorities— were hard won and enacted in South Carolina at least for a time. Cardozo’s example affirms that progress, though rarely a linear endeavor, is worthy of remembrance and pride.